Chapter 5.

Taken to Chugoku Military Police Headquarters

☆ Dutch POWs

In the Hundred -Year History of the Hiroshima Prefecture Police, it is written as follows about the POW camps in Hiroshima Prefecture:

On December 8, 1941, at the same time war simultaneously was begun declared against the US and Britain, it was decided to intern all the residents from the enemy countries, according to Japanese written war orders. In Hiroshima Prefecture as well, internment was imposed on all the residents from the enemy countries into the Police Stations of each district, early on the morning of that same day. They were regarded to have been engaged in anti-Japan activities of espionage and subversion, and were subjected to the internment. It was further decided to intern all those people in Chugoku and Shikoku areas in Hiroshima Prefecture. Accordingly, the Aikoen (Love and Light Hall) was established as the Internment Camp of the People from the Enemy Countries, in Miyosih-cho, Futami County. First Americans, and then Dutch people, were interned in this facility, and the names of the forty-four internees are still preserved in the Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

The Aikoen was in the middle of a vast rice-field, but in January 1942, when it became a Civilian Internment Camp, it was surrounded by a wooden fence. Isolated in that manner, a lot of residents of Miyoshi-cho never knew there were civilian internees held here until it was reported in magazine articles more than forty years after the war ended. The Aikoen was sited in the same lot where the current Miyoshi Aiko Day Nursery is located. It was originally a day care for children, but it was built to a large scale by an American, Mr. Huckabee. It was considered suitable to intern westerners of large physique. This camp was under the administration of the Home Ministry.

In this camp were interned Jesuit Father Ernest Goossens from Belgium, who established Elisabeth University of Music[1] after the war, eleven American Catholic sisters of Seishin Girls High School, which later became Notre Dame Seishin Women’s University, and others. They remained until they were forced to return to their home countries by an exchange ship, in September 1943.

After the civilian internees left, half the passengers of the Dutch Hospital Ship, the Op Ten Noort, which had been captured by the destroyer Amatsu-kaze in the southern sea, were sent to this camp in Miyoshi-cho from Yokohama via Fukuyama, passengers aboard the Fukuen Line train. The total number of them was forty-four: Captain G. Tuizinga, twenty crew members, six military medical doctors, one dentist, fifteen nurses and twelve male nurses. Those Dutch people who were interned in Miyoshi-cho were not treated as Prisoners of War (POWs), but it was regarded as a case of civilian internment. The reason was related to the process how they were captured.

[1] http://www.eum.ac.jp/cms/site_en.nsf/page/about/history.html

“The treatment of the Prisoners of War was under the charge of the Army; however, in the case of the internees in Miyoshi, they were mainly civilian refugees, therefore, different in nature from the camps for POWs only…”

After the surrender of Japan to the Allied Forces, the forty-four Dutch internees returned to their country in September 1945, leaving Miyoshi where they lived two years and nine months.

☆Hiroshima POW Camp

According to Domestic POW Camps of the Great Imperial Japan, edited with an Explanation by Yoshio Chaen, the first Hiroshima POW Camp under the regular/formal administration of the Ministry of War was established in Zentsuji-machi, Kagawa Prefecture. There, 320 POWs were held. Later that camp was moved into Tode Business School campus in Tode Village, Ashina County, Hiroshima Prefecture, and eventually nine branch camps were established under the Main Camp. In 1945, around 3,000 POWs were held in those camps, in forced labor.[1]

Hiroshima POW Camps

Main Camp: Tode Business School,Tode Village, Ashina County, Hiroshima Prefecture. (It was just the office and no POWs were held.)

Branch Camp 1 : Zentsuji-machi, Kagawa Prefecture : 110 POWs

Branch Camp 2 : Isoura, Niihama-City, Ehime Prefecture : 644 POWs

Branch Camp 3 : 448 Hibi, Tamano-city, Okayama Prefecture : 200 POWs

Branch Camp 4 : Nishi Village, Mukai-shima Island, Mitsugi County, Hiroshima Prefecture: 194 POWs

Branch Camp 5 : Sanjou-mura, Inno-shima Isand, Mitsugi County,Hiroshima Prefecture: 185 POWs

Branch Camp 6 : Omine-machi, Mine County, Yamaguchi Prefecture: 472 POWs

Branch Camp 7 : Ogushi, Ube City, Yamaguchi Prefecture: 283 POWs

Branch Camp 8 : Onoda, Onoda City, Yamaguchi Prefecture: 482 POWs

Branch Camp 9 : Ohhama, Onoda City, Yamaguchi Prefecture: 390 POWs

Total : 2,960 POWs

Following Zentsuji-machi, POW Camps were established in Niihama, Tamano City, Mukai-shima Island, Inno-shima Island, Omine-machi, Ube City, and Onoda City, where ship docks and coal mines in those areas needed work forces. POWs were transported from the southern sea, increasing the number of the POWs in those camps. Most of them were transported by ships. The actual number of the POWs who had been transported was much bigger than posted here; because of the attacks by the US submarines and air-raids on those ships, which had not been marked as carrying POWs, many POWs lost their lives while being transported to Japan.

I became interested in Hiroshima POW Camps. I asked Mr. Hap Halloran, who is a good friend of mine, and had been one of the B-29 POWs, if he knew some who had been in one of the nine POW Camps in Hiroshima. Then he introduced me to Mr. Benjamin Steele, a retired Professor of Art, who lived in the state of Montana. Mr. Steele sent a brief letter to me, dated June 2, 2002. According to his letter, he was captured by the Japanese and became a POW in Bataan, which is well-known because of the infamous Bataan Death March. Later, he was transported to Japan, entered the coal mine in Omine-machi, Mine County, Yamaguchi Prefecture, where he was forced to labor until he was liberated in September, 1945, after the end of the war. On his return to the US, he passed through Hiroshima City, which had been destroyed and presented a gruesome sight too terrible to look at. He enclosed a picture of himself and his comrades as emaciated POWs working as slave laborers.

☆Visit to Hiroshima by a Former Captain of a Plane

It was certain that more than twenty US airplanes were shot down in Kure Bay on July 28, 1945, including two bombers and many smaller aircraft carrier planes, although the exact number of them differs in the GHQ materials from that of the Hiroshima Prefectural Police.[2]

The issue here is about the twenty-five personnel who were aboard five aircraft. Nine of them were confirmed to have died from the fall of their plane, or died immediately after the fall. That leaves sixteen of them: eight of the nine crew members from the B-24 Bomber Lonesome Lady, those from the Taloa (including Dubinsky), two from the SB2C Helldiver, two from the TBM, and one from the Grumman Hellcat. They were captured, and were taken to Chugoku Military Police Headquarters as POWs, except for Abel of the Lonesome Lady. However, it is not clear if they went directly to the Military Police Headquarters; there is a possibility that some first were taken to Chugoku Area Army Headquarters. In the Military Police Headquarters, there was not enough space to hold such a large number of POWs. In fact, at the Headquarters, they had hurriedly converted an office into an internment room. It was situated on the inner right side, entering the front of the Headquarters. Therefore, while waiting for the room to be completed, the possibility is high that some had been in the detention room which was in Building No. 4 of the Chugoku Area Army Headquarters. Ms. Kikue Kono, who had been working for the Army Medical Department, says she had seen US soldiers, who had been in the detention room. Ms. Kono was the youngest female employee of the Medical Department, and witnessed seven or eight US soldiers in the detention room of Building No. 4. It was before the atomic bombing, but she is not sure about the dates.

According to the GHQ materials, eight US soldiers were taken to the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters on July 28: Dubinsky, Baumgartner, and Molnar, of the Taloa (for some reason he is listed in this material), Porter and Brissette of the SB2C, Brown and Lockett of the TBM, and Atkinson of the Lonesome Lady. Then on July 29, five more were taken there: Looper, Cartwright, Neal, Ellison and Long of the Lonesome Lady. Then two arrived on the next day, the 30th: Ryan of the Lonesome Lady and Hantschel of the Grumman Hellcat. Abel of the Lonesome Lady was not held here, as he had been held in Tokuyama on August 4.

In 1999, former 2nd Lt. Thomas Cartwright, a war-time pilot-in-command of a B-24 bomber, visited Hiroshima, and I guided him around the city. At that time, he saw the former site of Chugoku Area Army Headquarters, and witnessed, “I was interned here.” Building No. 1 of Chugoku Area Army Headquarters used to be at the current site of the Gokoku Shrine. Buildings No. 2 and No. 3 were located east of Building No. 1, and Building No. 4 was behind No. 2, currently in the inner-most place when viewed from the bridge in front of the Secondary Enclosure of the Hiroshima Castle, Ni-no-Maru. Let me add that, after the atomic bombing, Long was witnessed to have been dead [nearby, at the elementary school previously attended by the author, S. Mori (Editor's note)].

According to the GHQ materials, the US POWs were all directly delivered to Maj. Seizo Satoh of Chugoku Military Police Headquarters, not to Chugoku Area Army Headquarters. Per military protocol, the army headquarters of the area should have been in charge of the POWs. However, there is indication that it was not a staff officer of the Second General Army at the Chugoku Area Army Headquarters, but rather Lt. Col. Shigeo Nakamura of Chugoku Military Police Headquarters who dealt with the matters of the POWs. Nakamura probably had this responsibility because the Army Headquarters of Hiroshima was not a large organization.

Both Col. Imoto and Lt. Col. Kakuzo Ohya of the Second General Army remained silent about their involvement with the POWs. Lt. Col. Masaharu Kikkawa had even dared to conspire in a cunning maneuver by reporting that POWs who actually died in distant Kyushu were killed in the Hiroshima atomic bombing.

Lt. Col. Ohya of the Second General Army had been dispatched to Hiroshima from the Imperial Headquarters on an extended official trip. He left the ten B-29 crewmen who had been captured as POWs in Hamada in the hands of Hiroshima Military Policeman 1st. Lt. Nobuiti Fukui, ordering Fukui to take them to Ujina.

Originally, Ohya said, “POWs shouldn’t be kept alive!” thus ordering their execution––against which 1st. Lt. Fukui protested, risking his own life. The POWs never forgot his deed, and they sent from the U.S. a bouquet of flowers to Fukui on his deathbed, as a token of their gratitude. Those who knew most about the U.S. POWs who had been transported to Hiroshima City hid the facts, which made it difficult to learn what happened to the U.S. POWs who were exposed to radiation from the atomic bombing.

What Happened at the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters?

Chugoku Military Police Headquarters was just 400 meters away from the epicenter, which can be defined as within a very close range. However, some military police personnel who were stationed here survived because they traveled away from the bomb epicenter. According to the documentation made by the Headquarters about the time of the atomic bombing, three survived because they had been dispatched to Tokyo and the other two survived because they had been away from the Headquarters and further from the epicenter, although they had been exposed to radiation elsewhere in the city. The group who were in Tokyo were Akitaka Fujita, Susumu Matsumoto, and an unidentified person. Those who had been exposed to radiation inside the city were Makoto Ohtsuka and Takashi Morita. Thanks to those survivors, I could learn what happened at Chugoku Military Police Headquarters in some detail, through interviewing Messrs. Fujita, Matsumoto and Morita in person, and reading the memoir of Mr. Ohtsuka.

This sketch depicts the Kempeitai's Chugoku MP HQ in Hiroshima,including the floorpan of all or some of the first floor of the main building where the American POWs were held in July and early August. 1945. The sketch was made from memory by Akio Nakamura, the son of Lt. Col. Nakamura.

Military Police Personnel Matsumoto was then Chief Officer (Capt.) of the Foreign Affairs Counterespionage Section of Chugoku Military Police Headquarters, and was engaged in the duty of directly dealing with POWs. The Military Police Personnel Fujita, Matsumoto and others obtained crucial information during the interrogation of the POWs, which had been conducted several days before the atomic bombing, around August 1 or 2. It was the information that Hiroshima and the cities located further west were protected from bombardment by US military orders. MP Matsumoto knew instinctively that Hiroshima would be hit by a major air raid. That was why Matsumoto traveled to Tokyo on August 5, in order to report the information to Tokyo Military Police Headquarters. During the absence of MP Matsumoto, his subordinate Warrant Officer Matsubara, conducted interrogations of the POWs, which he documented. However, both Warrant Officer Matsubara and the records he left were turned into ashes by the atomic bomb.

Fortunately, MP Matsumoto remembered some fragments of the contents of the interrogation, which he conducted through an interpreter. According to him, the person in charge of the interpretation of the interrogation was female, which was a rare case. First she warned in advance that she did not know military terminology. Therefore, MP Matsumoto spoke in civilian terminology, which he asked her to interpret. The POW he interrogated was a crew member of the bomber which was shot down into the sea off Kure City. This POW confessed that he had seen an announcement on the notice board at the Okinawa Base, which read “Hiroshima and the cities located further west of it have been appointed as the cities under the ban from bombardment.” Presuming from materials available, it seems to have been the Prohibition Order of Bombardment of Hiroshima, Kokura, Nagasaki and Niigata, which was issued on July 25. Another POW did not know it was Hiroshima where he was, and told Matsumoto that he “arrived in a boat”. He seems to have been one of those who were aboard planes that departed from aircraft carriers. That POW, when he was offered coffee during the interrogation, declined helping himself to sugar, saying “No sugar”. MP Matsumoto recalled these scenes.

The POWs of the bombers carried with them items such as a mirror, which helped to send signals to other US planes during the flight: a flashlight, and a dye to change the color of seawater so that it would be visible for rescue operations from the sky.

Having realized the seriousness of the information provided by a POW, the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters might have placed a direct telephone call to the Main Headquarters. The information might have been forwarded to the Chugoku Area Army Headquarters through the Imperial Army Ministry. That would initiate the Preliminary Warnings and Air Raid Warnings in Hiroshima. I regret that phone call never occurred. Had it happened, the number of the atomic bomb victims might have been reduced to some extent.

Coincidentally, within a day of that interrogation (~2 August), the official decision was made for Hiroshima to be the first target of the atomic bomb.

☆Isaw POWs in the prison cells!

August 5, the day before the atom bombing. On this day, two men saw the POWs with their own eyes. Mr. Akio Nakamura, former Professor of Osaka Municipal University, and Mr. Kazushi Higashida.

Lt. Col. Shigeo Nakamura, in command of the Chugoku Military Police (Kempeitai) Headquarters.

Mr. Nakamura is the son of Lt. Col. Shigeo Nakamura, who was one of the executive officers of the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters. Akio Nakamura was a thirteen-year-old student of the First Hiroshima Junior High School (currently Kokutaiji High School.) He has written about that occasion in his memoir, The End for My Father and the US POWs. According to the memoir, the father, Shigeo, came home, after a long absence, in the evening of August 4, two days before the atomic bombing. In fact, Mr. Nakamura’s father was transferred to Chugoku Military Police Headquarters from Tokyo in March, 1945, and thus had moved to Hiroshima. Until then Mr. Nakamura and his younger brother had been separated from their father, and were living with their grandmother in Otsu City, Shiga Prefecture, which was the father’s homeland. Ironically, the worsening war situation had brought the family together again. The family was living in Rakurakuen (current Saeki-ku, Hiroshima City) in the suburbs, and the father was extremely busy. He usually stayed in the city, coming home just a few days per month. Therefore, on that day, Mr. Nakamura talked to his father earnestly. He told him that he went to see an enemy plane that was shot down, and also about the POWs. Father said, “Other than those you have seen, a number of POWs had been captured, and we had an extraordinary situation. All the detention rooms in Hiroshima are full of POWs. My, they are huge!” and he gestured stretching his hand over his head, showing how tall they were. Usually, he talked little about his work at home, but on that day he was willing to. The impression of the POWs must have been strong in his mind as well.

He went on talking. The initial problem was to find accommodations for the POWs. There were no POW camp facilities in Hiroshima City, so the only option available was using detention rooms, called eiso, which each military unit had. However, those were cells to hold separately the soldiers who had committed crimes, so the number was limited. The Military Police Headquarters, of course, had the eiso, but it could not possibly hold all the POWs. They asked each army unit in Hiroshima City to accommodate the POWs separately, however, still there were not enough facilities. Therefore, they had an idea, and decided to make Tokyo receive some of the POWs. There were some other reasons for this issue. One of the POWs was an officer in command. Another one, when he parachuted down, shot and killed a farmer. Those two should be taken to the main headquarters for further interrogation. The two should have been 1st Lt. Thomas Cartwright and Sgt. Hugh Atkinson; however, those who were actually taken to Tokyo were Cartwright, Brown and Lockett.

While he was listening to his father’s story, Mr. Nakamura was eager for the chance to see some POWs. So he asked his father, fully expecting to be denied. Probably his father was in a good mood because of the relaxed family reunion after quite some time. He did not say no.

The next day, August 5, because his work at the factory finished fairly early, Mr. Nakamura passed by his home and hurried to Chugoku Military Police Headquarters in Hiroshima City. Fortunately, his father was in the office. He looked a little surprised to see his son, as if he had never expected him to really show up. He said, “As you’ve come such a distance, you can come with me, but for a short time.” The detention rooms were situated at the long end of the corridor in front of his father’s room. The Headquarters were a two-storied wooden building, and the detention rooms were on the ground floor, being on the right end when you stood facing the front of the building. In the corridor of the detention rooms, a soldier on guard was sitting in a chair, but when the father approached, he stood up and bowed. There were five cells next to each other, each of which was narrow being two or three tatami mat affairs. The ceiling was high, the floor was wooden, and the front of each cell was enclosed with thick wooden bars.

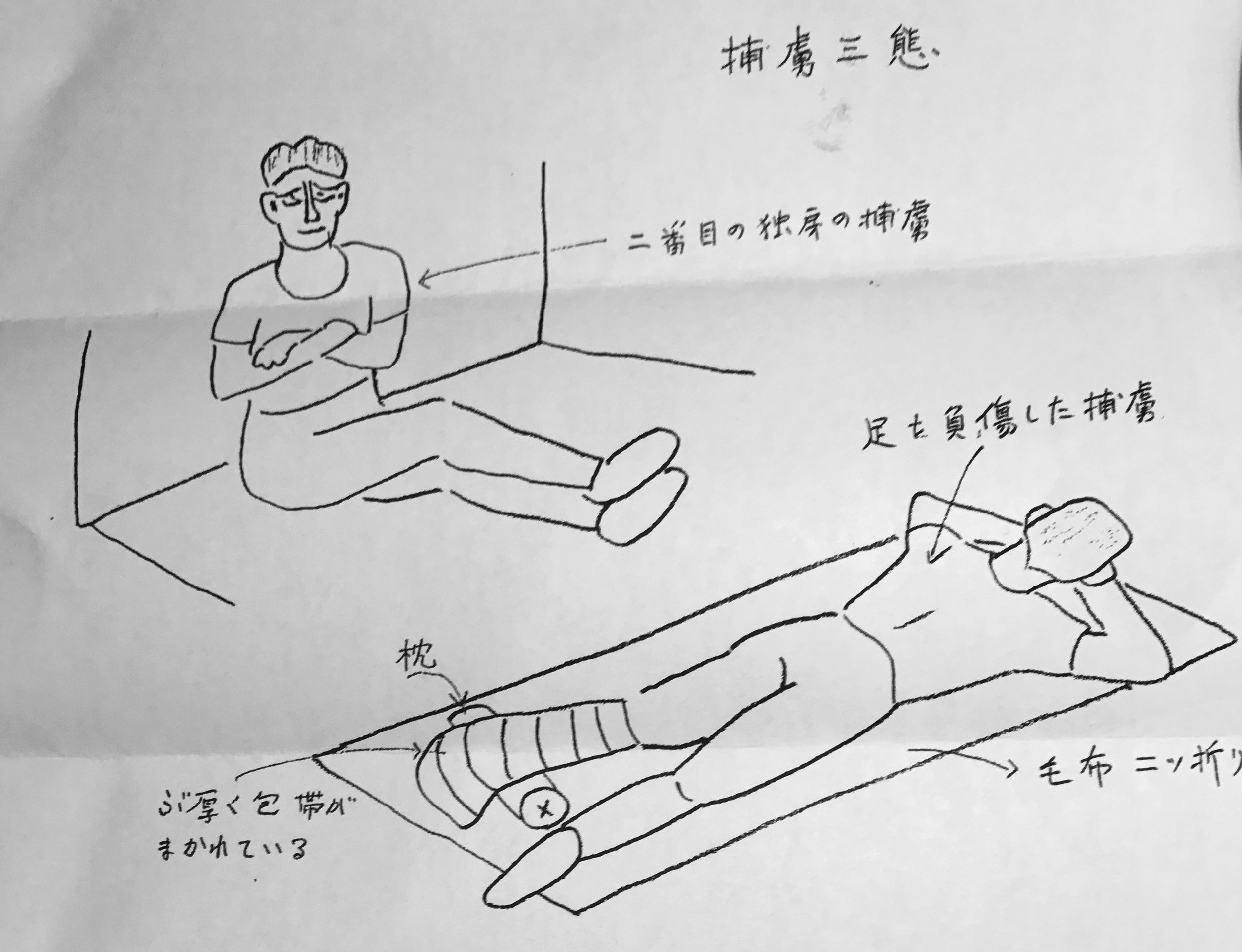

Sketch by Professor Akio Nakamura of two of the American POWs he saw in the Chugoku MP Headquarters on 5 August, 1945. The lower figure with the injured leg is most likely Durden Looper, who was known to have a leg injury. (Editor's note: Tom Cartwright believed them to be Hugh Atkinson, sitting, and James Ryan on the pallet with an injured foot.) Professor Nakamura's father was at the time a child, the son of Lt. Col. Shigeo Nakamura the commanding officer of the MP HQ. He, too, perished in the bombing. (Courtesy Dr. Akio Nakamura.)

The POW who was in the first room had reddish hair, with a mustache, and had tattoos on his arms, as Mr. Nakamura remembers. He was in an undershirt with short sleeves, and was leaning on the baseboard with his arms folded. The POW in the next cell was exactly in the same posture, but his hair was dark and coarse and looked a little grayish because of the light or gray hairs he had. He was totally expressionless, and was staring at Mr. Nakamura in the face without blinking his eyes. The color of his eyes were also grayish, and impressive for Mr. Nakamura, as he had thought all the Westerners had blond hair and blue eyes. He left him a strong impression because of that. The guard told him the two POWs were both noncommissioned officers. The third POW had a leg injury. On the floor was spread a military blanket folded double, and he was lying diagonally on his stomach. Mr. Nakamura does not remember which leg it was, but it seemed quite a serious wound, as his leg was thickly dressed from the toes, ankle, to below the knee, and a military pillow, looking like a tea caddy, was applied. His face was hidden, but from the look of his back, he seemed like a man of stout frame. Then the guard said, “There is another who is wounded. Probably, this one,” and he called at the fourth cell, “Porter”.

Mr. Nakamura had not realized until then, but in front of each cell was attached a piece of paper in which POW’s names were written in the Japanese katakana sign, the sign which is applied for anything from the Western language. Porter was sitting with his back rounded, holding both knees in his arms. As his name was called, he replied “Yes,” in a voice that carried well, and stood up. “This POW is a First Lieutenant.” The guard unlocked the small entrance in the front, and prompted Porter to come out. Porter stood in the corridor, bare-footed, in trunks and undershirt. He looked rather smallish and slim for a Westerner. He seemed a bit nervous about the presence of Nakamura’s father, and while the guard took his arm, examining his wrist, he was frequently watching the face of the father. However, it did not seem he was injured.

When Nakamura’s father asked the guard about the meals of the POWs, he answered, “We provide them rice balls and miso-soup. Everyone eats rice balls, but they rarely eat miso-soup.” The father stood with his arms folded, his face a little bent down, in a pensive mood. At that time, the food situation in Japan was quite awful, and even the Army was not an exception. Mr. Nakamura had once been entertained with a meal for soldiers, but it was a meager meal of some rice with barley in it, and sliced dried daikon (Japanese radish) seasoned with soy sauce. It must have been particularly severe for those POWs, who had been accustomed to a different diet. During their conversation, Porter was busily comparing the facial expressions of the two men, as if he had been trying to search what intentions they had.

Sketch by Professor Akio Nakamura of of an American POW Raymond Porter, who he saw in the Chugoku MP Headquarters on 5 August, 1945. (Courtesy Dr. Akio Nakamura.)

Mr. Nakamura was looking at Porter’s face in profile, and when their eyes met for an instant, he left Nakamura an impression being like a naive university student rather than a military personnel. However, the movement of Porter’s eyes sometimes came back in the memory of Mr. Nakamura even later in his life. Different from his look at Mr. Nakamura, when he looked at his father and the guard, the movement of his eyes was surprisingly quick and sharp. Mr. Nakamura wondered how he could move the eyes that fast. When he learned that Porter was a bomber pilot, Mr. Nakamura understood why. 1st Lt. Porter left the strongest impression with Mr. Nakamura.

In the fifth, the last cell, Mr. Nakamura thought he had seen a similar figure of a person, but at that time, his father said, “Well, that would be enough,” and started going back to his office. Mr. Nakamura hurriedly thanked the guard, and followed his father. So he remembered nothing about the last room. When he reached the father’s office, his father had already sat in his chair, reading the documents on the desk. The boy Nakamura stood at the entrance of the room and asked, “Now I’m going home. Is there anything you’d like me to bring back home?” Father said, still looking at the document, “Nothing particular. I’m leaving again on a duty trip tomorrow in the morning.” Indeed, the father reading some documents was the last image of him the son would see.

After half a century later, I let Mr. Nakamura see the group photo of the crew of the Lonesome Lady, to see which of them were those he had seen in the detention rooms. It was Atkinson who he instantly recognized. He firmly said the second man he saw in the cell was Atkinson. He also said the POW in the third cell, who had been injured, was possibly Looper, however, he avoided affirming that.

Another person saw the POWs right before the atomic bombing. It is Mr. Kazushi Higashida, a former executive director of a company. In 1944, Mr. Higashida, who had been a student of Kobe Commercial College (currently Kobe University), was stationed at the General Staff Section of the Second General Army Headquarters at the north exit of Hiroshima Station. He was a Non-commissioned Officer, through the wartime mobilization of students for military service. In the morning of August 5, a request came from Chugoku Military Police Headquarters to interrogate some US POWs. So he went, accompanied by an interpreter. Around one o’clock in the afternoon, they met two US military personnel. One was a 2nd Lieutenant and another was a sergeant, according to his memory. On that day, they interrogated just the 2nd Lieutenant.

He was around 180cm (5’9”) tall, and looked like he was twenty-two or three. He was a handsome guy of reddish hair, wearing a flying suit. After around an hour of interrogation, they started up a chat. He said, “I’m a student soldier, and was studying economics at a university”, so Mr. Higashida, who also had been a student of economics felt close to him, and asked him about his girlfriend. He took out a photo from his breast pocket and showed it to him. It was a girl in a white dress. Responding to his question, about any problems he might have, the soldier complained about mosquitos, which bit him during the night; so Mr. Higashida instructed the military police at the headquarters to give him a mosquito coil, and they departed.

☆Those Who Survived

Some POWs were sent to Tokyo, while others remained in Hiroshima. That separated their fate. Those who were sent to Tokyo were those who had been expected to have information about the US forces. Among those who were in Hiroshima were Cartwright, pilot-in-command of the Lonesome Lady, and two US naval personnel.

In Hiroshima, each area Army headquarters had received a message in Morse code from Tokyo. The summary of it was as follows: The POW camps in Tokyo are full. Therefore, all the enemy aircrew do not have to be sent to Tokyo. However, only the commanding officers who have valuable information must be sent to Tokyo. About the remaining members, each area Army Headquarters should deal adequately with them. The instruction was such in content.

Let’s consider how the transfer to Tokyo from Hiroshima occurred by quoting from Cartwright’s book:

The next morning[3], when I was taken out of our cell and away from my crew and blindfolded and tied for the trip, I felt a little sorry for myself. I was joined with the two American navel personnel and taken to a train station[4]. The train trip took most of two days with many delays and a layover one night in a bare room in a place that I later learned was in the city of Osaka… We were taken to what was obviously a military base, and put in separate cells in what appeared to be a brig for the base, but no other prisoners were in this fairly small building. The cell had wooden bars, no window, and a dim light hanging from the ceiling that burned throughout the night.

Cartwright wrote, “I learned later that the location where I had been held was the Imperial General Headquarters located in Tokyo.” The treatment there was similar to that in Hiroshima. He was given a threadbare blanket. There was a guard in the corridor. Meals consisted of only a softball-size rice ball and water. There was no bath, and he was allowed to stand up only for using the toilet and for interrogation. As they had been curious about white POWs, a lot of Japanese visited the cell. They stared at Cartwright with a look of watching something strange. One kept looking for an hour. Although the guard had no intention to permit those onlookers to get in, the number of them was so large for the guard to deal with.

Why were Lockett and Brown of the TBM Avenger, who are mentioned in Cartwright’s book, taken to Tokyo? Cartwright was a commander-in-charge of a plane, so he was expected to know some secret information of the US forces. Therefore, he was sent for interrogation to Tokyo. However, the other two were just the crew members of a small plane. Therefore, they should not possibly have been able to acquire important information. However, they were taken to Tokyo. Until recently, it was said that the reason for their transfer was because they belonged to the US Navy. However, this is not reasonable. Like the TBM Avenger, the SB2C Helldiver belonged to the US Navy, yet those Navy crew members, Porter and Brissette, had not been sent to Tokyo.

I presume that it was never the plan to send Locket and Brown to Tokyo. I think that the intent might have been to send Atkinson and Ryan of Lonesome Lady. Atkinson parachuted down when the plane was shot down, and he killed a Japanese farmer by shooting him. Also, Ryan came down at the same area as Atkinson at the time their plane crashed and he hid out in the mountains. Therefore, he should have been under suspicion of shooting and killing the farmer. However, in Hiroshima, they were put in a big room, because of the shortage of holding cells. In short, I presume that they had been misidentified as Lockett and Brown at that point.

It is not only a presumption, but there is a reason for this thinking. Maj. Col. Nakamura, who had been mentioned, was the Kempeitai personnel dealing with the U.S. POWs at the Military Police. His son, Mr. Akio Nakamura, was interested in them and asked various things of his father. Maj. Col. Nakamura replied as follows: At the moment, too many POWs have been taken to Hiroshima, and we have no means to accommodate them. So, I’m thinking of sending them to Tokyo by all means. Particularly, we have a captain of an airplane, and a U.S. POW who shot a farmer. If we hold a military court for them, it will take too much time. Therefore, I will send the captain and that POW to Tokyo as soon as possible. That is the reason I wonder if Lockett and Brown had been sent to Tokyo, because they had been mistaken for Atkinson and Ryan.

Cartwright, the commander of the Lonesome Lady, had told the crew that should they be captured by the Japanese, they could tell them their name, rank and unit, but did not have to reveal any personal information. He had also advised them to avoid being captured by civilians rather than by military personnel, because military men would not dispose of POWs on their own accord, but civilians sometimes lynch them. However, in the case of Atkinson, because the farmers came running after him with a hunting gun, he thought he would be shot. Therefore, he responded with his gun.

If my presumption was right, Lockett and Brown were able to survive because Atkinson fought with his gun.

[1] Editor’s note: POW Camps are posted in Mr. Toru Fukubayashi’s Report on the POW Camps in Japan Proper:

http://www.powresearch.jp/en/archive/camplist/index.html]

[2] The POW Research Network of Japan reports that a third B-24, (#44-42127, nicknamed Boots, 43rd Bombers Group) was hit by anti-aircraft artillery fire crashed while returning from the 28 July bombing raid on Kure Harbor http://www.powresearch.jp/en/pdf_e/pilot/chugoku_shikoku.pdf. All crew members died, but are not included in the discussion that follows. Their names are listed at http://www10.ocn.ne.jp/~kuushuu/B24-44-42127.html. The Accident Report listed the plane went down in “Saganoseki at sea”, http://www.accident-report.com/MACR/1945/m194507.html

[3] Author’s note: this might have been the morning of July 31

[4] Author’s note: On July 28, 1945, the TMS Avenger torpedo carrier bomber, which departed from the US Carrier Wasp was shot down off Ninoshima Island. 1st Lt.[?] Joseph Brown, the pilot, and Sgt. Frederick Lockett, the radio operator and gunner, also were taken to Chugoku Military Police Headquarters. They both returned to the U.S. after the war.